stilted and formal

sparingly: in a restricted or infrequent manner; in small quantities.

euphemism: softening; genteelism.

circumlocutions: indirectness; the use of many words where fewer would do, especially in a deliberate attempt to be vague or evasive.

eradicate: destroy completely; put an end to.

tactfully: with skill and sensitivity in dealing with others or with difficult issues.

discourteous: showing rudeness and a lack of consideration for other people.

brevity: be brief

conciliatory: intended or likely to placate (make (someone) less angry) or pacify(calm).

superfluous: unnecessary, especially through being more than enough.

courtesy: the showing of politeness in one’s attitude and behavior toward others.

verbiage: speech or writing that uses too many words or excessively technical expressions.

Euphemisms are a form of vagueness: at best they use more words than a direct statement and at worst, because of their lack of directness, they can be misunderstood. They also give the impression that you are trying to hide something. So do not say, ‘Profits showed a negative trend’ when you mean ‘We made a loss’, or even when you mean ‘Profits were down on last year.’ Not only does it sound as though you are trying to hide your poor performance behind the euphemism, but as we have seen, it could mean

either of two things.

It is not only euphemisms that can sometimes be ambiguous. Even apparently straightforward words and sentences might be capable of being understood in more than one way. So if, for example, you use the word ‘sales’, is it clear from your context whether you mean sales value or sales volume; and can people tell whether ‘improvement in profitability’ means increased profits or higher profit margins?

You should also not say something like ‘I need to know what our costs will be by the end of this month’ if you mean ‘I need to know by the end of this month what our costs will be.’ In the first sentence, ‘by the end of this month’ refers to the costs, not to when you need to know.

There are three main causes of wordiness in business communications:

● circumlocution

● vague qualifiers

● padding

sounds pompous and long-winded

pompous: affectedly and irritatingly grand, solemn, or self-important.

long-winded: (of speech or writing) continuing at length and in a tedious way.

vague qualifiers as fillers:

You also need to be careful; although most expressions like this are unnecessary, some can serve a useful purpose. For example, ‘You will appreciate that …’ sounds like padding, but it can be used to get the reader on your side. For example, if you want to explain why you are unable to give a customer a higher discount, you can say: ‘You will appreciate that our discounts are already generous. Our margins are therefore already tight, and any increase in discount would erode them yet further.’ This appeals to your

customer as a reasonable and intelligent person who will understand these problems. So although ‘You will appreciate’ is really padding, it does serve a purpose.

Techniques for Achieving a Conversational Tone in Letters

● If possible, address your correspondent by name.

● Make the letter personal – from you, rather than the company – so use ‘I’ rather than ‘we’.

● Avoid formal expressions such as ‘We acknowledge receipt‘.

● Use the active rather than the passive voice: ‘I have made enquiries’, rather than ‘Enquiries have been made.’ The former sounds friendlier, the latter less personal.

● If you are in the wrong, admit it and apologise.

● If your correspondent is in the wrong, say so tactfully and politely.

Not only will your tone change according to the nature of your document, it will also be different for different readers. For example, a request to your Managing Director might be expressed as follows: ‘I wonder whether you would agree to the company paying something towards the staff’s Christmas party this year.’

On the other hand, a request to a subordinate might be expressed differently: ‘Please could you let me have the costings for the product launch by next Tuesday?’

By emphasising the positive and perhaps trying to ameliorate (make (something bad or unsatisfactory) better.) any negative aspects your communication will come over as positive, which will help to get the reaction you want. For example:

Say ‘If we receive payment within that time, then we can both be spared the unpleasantness of legal action’, rather than the more negative ‘If we do not receive payment within that time, then we will be forced to take legal action.’ The result is a positive, polite, yet forceful letter, which is far more likely to achieve the result Lionel wants than a rude, negative one.

You should say ‘buy’ rather than ‘purchase’, and ‘try’ rather than ‘endeavour’. And never use a word unless you are sure you know exactly what it means – you could be saying something very different from what you intended!

There are four common faults that will make your communication seem either longwinded or sloppy:

● jargon

● tautology (the saying of the same thing twice in different words, generally considered to be a fault of style)

● unnecessary abstract nouns

● clichés

Jargon is technical language that is specific to a group or profession. Sometimes it is necessary, especially in the scientific and technical fields. Even in business writing, there may be times when you need to use a technical term that is clearly understood. But most business jargon simply complicates your communication. You must differentiate between acceptable business vocabulary (such as ‘contingency planning’ or ‘bill of exchange’) and ‘management-speak’ (such terms as ‘interface’ and ‘downturn’). You should also avoid ‘commercialese’ (expressions like ‘we are in receipt of’ and ‘aforementioned’). Do not even use acceptable jargon with lay people unless you are certain they will understand what you mean.

Most abstract nouns sound vague and often pompous. They also usually have the effect of making your communication long-winded. Particularly bad are nouns derived from verbs. There are examples of these in the following:

● The reconciliation of your account is in progress. (Your account is being reconciled.)

● The achievement of our sales target will not be possible without greater effort on your part. (We need greater effort on your part to achieve our sales target.)

● A quick settlement of your account would be appreciated. (Please settle your account quickly.)

Clichés are expressions that have been used so often that they have become old and overworked. They will make your communication seem artificial and insincere, giving the impression that you could not be bothered to think of an original expression. Here are some examples:

● Be that as it may …

● Needless to say …

● I have explored every avenue.

● The fact of the matter is …

● Far be it from me …

● Last but not least …

You should avoid using ‘etc’. Your communication should be specific, and ‘etc.’ gives the impression that you do not know all the facts or are too lazy to give them. If the list of things you want to mention is too long, use ‘for example’ or ‘such as’, rather than ‘etc.’ So instead of ‘We need to discuss discount, payment terms, minimum order quantities, etc.’ you should say, ‘We need to discuss issues such as discount, payment terms and minimum, order quantities.’

Tips on Speaking Clearly

● Make notes of what you want to say, including particular words and phrases that might clarify your points.

● Go over those notes before you begin to speak so that you have a good idea of what you are going to say and how you are going to say it.

● Have your notes with you when you speak to help you in case you are stuck.

● Speak slowly and in a clear voice.

● Do not ‘waffle’; you should be brief and to the point, as you are when writing.

● When involved in a conversation, confirm at particular points that you have understood what the other person has said so far. And do not pretend to understand something you do not.

● Indicate by your tone of voice the impression you are trying to convey – apologetic, conciliatory (tending to lessen or avoid conflict or hostility), firm, enthusiastic.

● Always be polite – even if the other person is rude, do not allow yourself to be drawn into a slanging match.

● Pause at appropriate moments in order to break up what you are saying and give your audience an opportunity to ask questions.

Certain types of communication, however, cause particular problems and therefore warrant special attention. These are:

● requests

● sales letters

● meetings

● complaints

● complex problems

● reports

● presentations

obsequious: too eager to praise or obey someone; flattery.

sycophantic: behaving or done in an obsequious way in order to gain advantage.

commensurate: corresponding in size or degree; in proportion; equal.

Tips for Making and Answering Requests

● When making a request, be friendly and courteous.

● Give the background to your request or your reasons for making it first, and build up to the request itself.

● When agreeing to a request, do so early in the document or conversation.

● When refusing a request, give your reasons first, then your refusal.

● Do so politely and offer some kind of consolation or hope if possible.

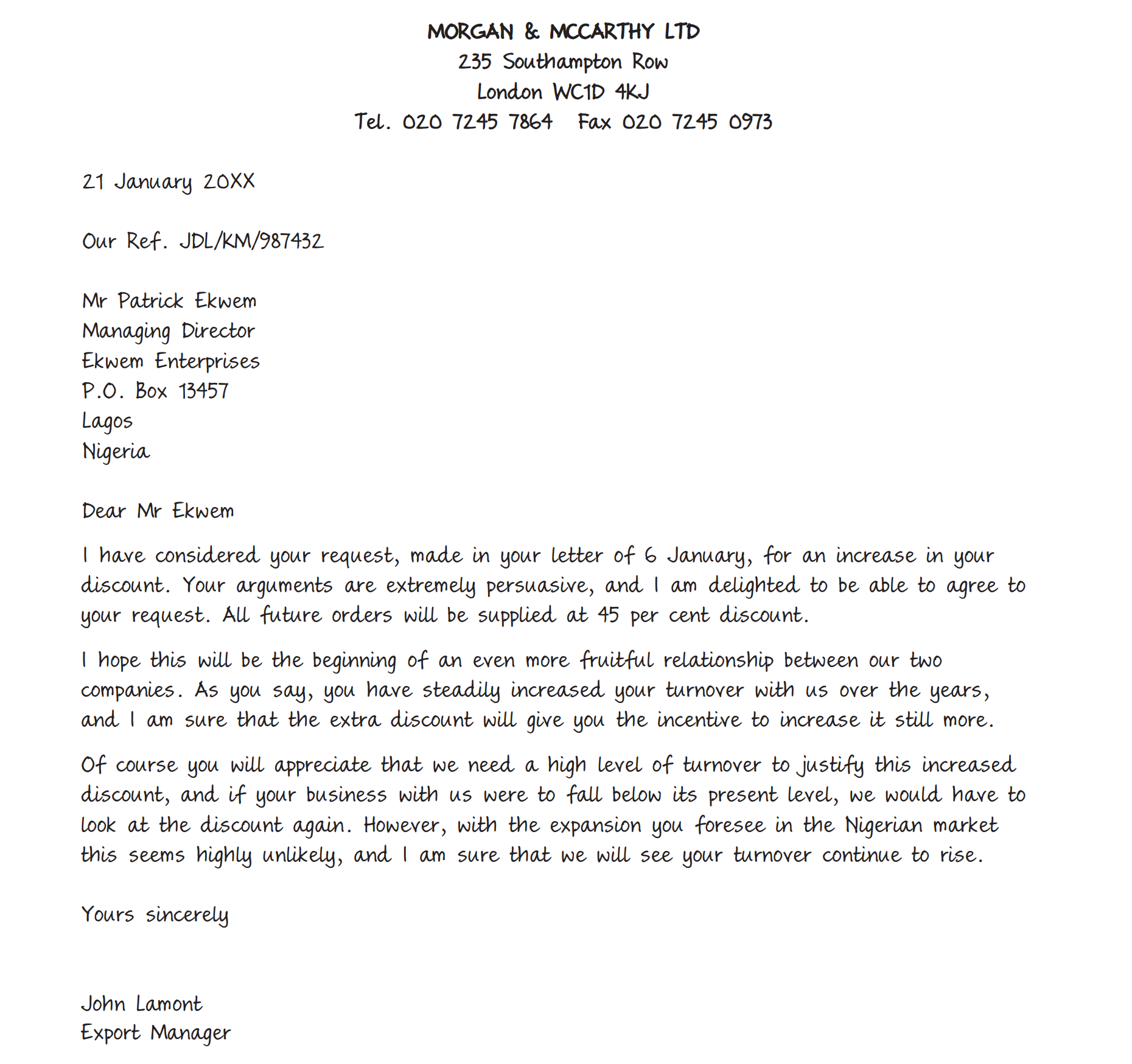

Agreeing to a Request

Answering requests: say ‘yes’ quickly, say ‘no’ slowly.

If you agree with the request, then you should say so immediately. Your aim is always to make a good impression, and to do so as soon as possible. Agreeing to the request should make you very popular, so do it at the start – preferably in the first paragraph, but certainly no later than the second. If there are any strings attached to your agreement, they should come later rather than diluting the good first impression.

The effect of giving the good news immediately will be wasted, however, if you are grudging or high-handed about it. If you sound as though you are doing the other person a great favour, or are acceding to the request grudgingly, you will make quite the wrong impression. Try to sound as though you are pleased to be able to agree.

Refusing a Request

Build up to the refusal gradually. Express an understanding of the other person’s problem, explain the lengths you have gone to to find a way of solving it,give the reasons for your refusal, and then say ‘no’. As with agreeing, your aim is to make as good an impression as possible. Building up to your refusal gives you a chance to get the other person at least to understand your position before the disappointment of being turned down.

Once again, this impression can be spoiled if your tone is wrong. Do not think, just because you are in control when refusing a request, that you can be insulting or impolite. Always be courteous when turning someone down. Not only is it good manners, it is also in your own interests. If you are refusing a subordinate, it makes sense to try to lessen the disappointment and not to demotivate him or her. And if it is a member of the public or a client, you have your organisation’s image to consider.

For the same reason, see whether you can somehow soften the blow by offering some hope for the future, no matter how tenuous. You could just say, ‘I will get back to you if the situation changes’ or ‘I will keep your letter on file’ or you could offer something specific for the other person to aim for.

grudging

high-handed

incentive: a thing that motivates or encourages one to do something.

proviso: an article or clause (as in a contract) that introduces a condition

tenuous: very weak or slight.

imply: strongly suggest the truth or existence of (something not expressly stated).

drab: lacking brightness or interest; drearily dull.

horticulturalist: an expert in or student of garden cultivation and management.

ambience: the character and atmosphere of a place.

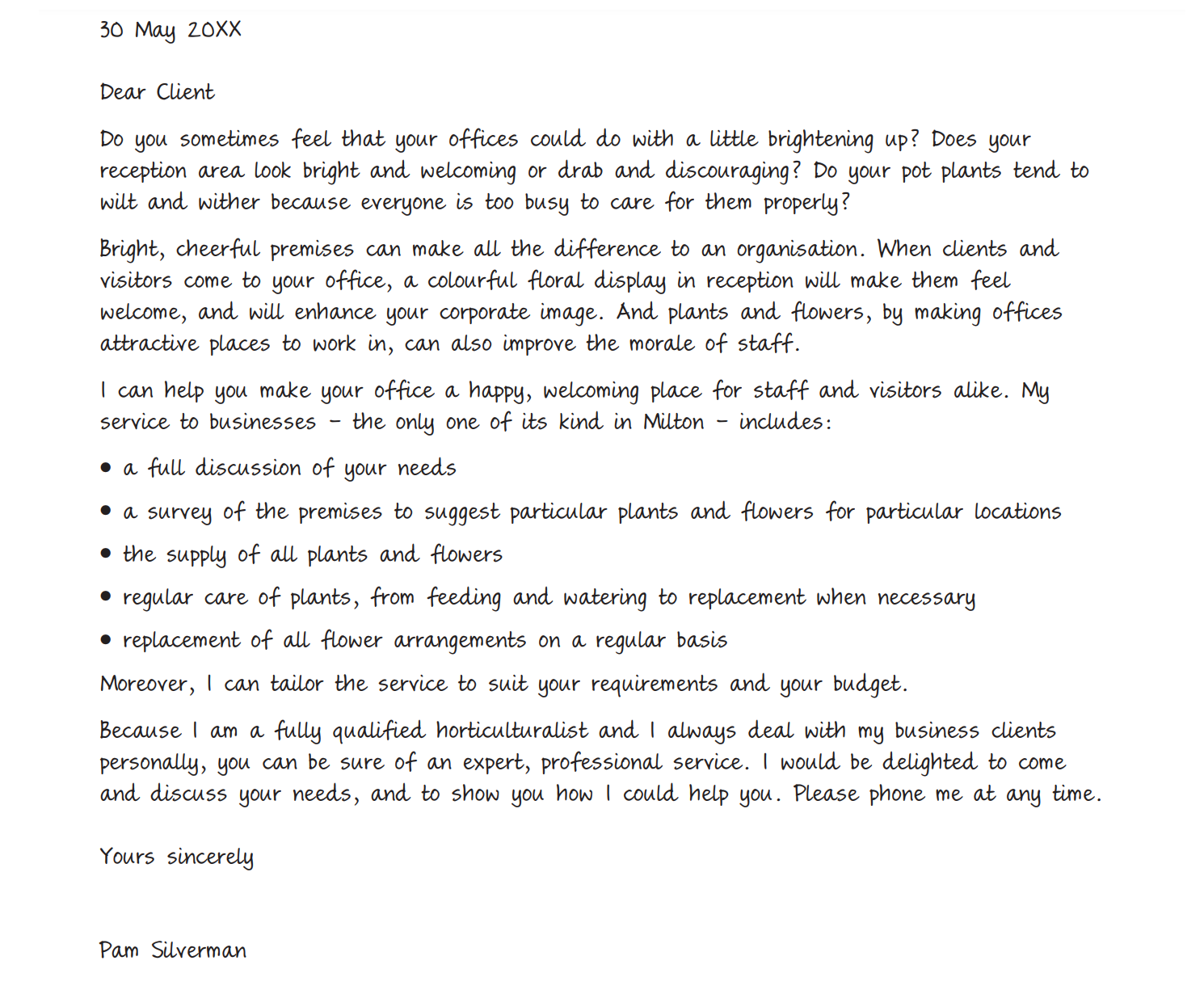

A Sales Letter

Unique Selling Propositions and Emotional Buying Triggers These are two concepts in advertising that can be useful when writing sales letters.

● A unique selling proposition (USP) is simply jargon for something that makes your product or service unique, something you have that your competitors do not. In the case of Pam Silverman’s florist’s shop, it is the fact that she will not only supply flowers and plants to businesses, but also ensure that they are cared for and replaced from time to time. It is not essential to have a USP, but if you do have one, then make a point of it in your letter. Do not, however, try too hard. There may be a feature of your product or service that is unique to you, but which is relatively unimportant; if you place too much emphasis on such a feature it could be counterproductive. So if, for example, you are promoting a range of paints, the fact that you have one more colour in your range than your competitor’s could be seen as a USP, but it is unlikely to persuade your readers to buy your paints rather than theirs.

● Emotional buying triggers are appeals to your readers’ emotions and instincts. The need to be liked, to project the ‘right’ image, to achieve, to feel secure, to be an individual – all of these can trigger a positive response if they are given the right stimulus. But, as with USPs, they should not be forced.

AIDA comes directly from advertising, and is a way of remembering the order in which

you should present your case. The letters stand for:

– Attention

– Interest

– Desire

– Action

In other words you should first aim to attract your readers’ attention. Then you must hold their interest. Next you need to convert that interest into a desire for your product or service. And finally you should indicate what action you want them to take.

● The four Ps are:

– Promise

– Picture

– Proof

– Push

With this approach, you promise the reader certain benefits. You create a picture showing how he or she will gain those benefits, prove that you can deliver them, and then provide a ‘push’ to action. Unlike AIDA, it is not essential to stick to this order, although the ‘push’ should usually come last.

indicate: point out; show.

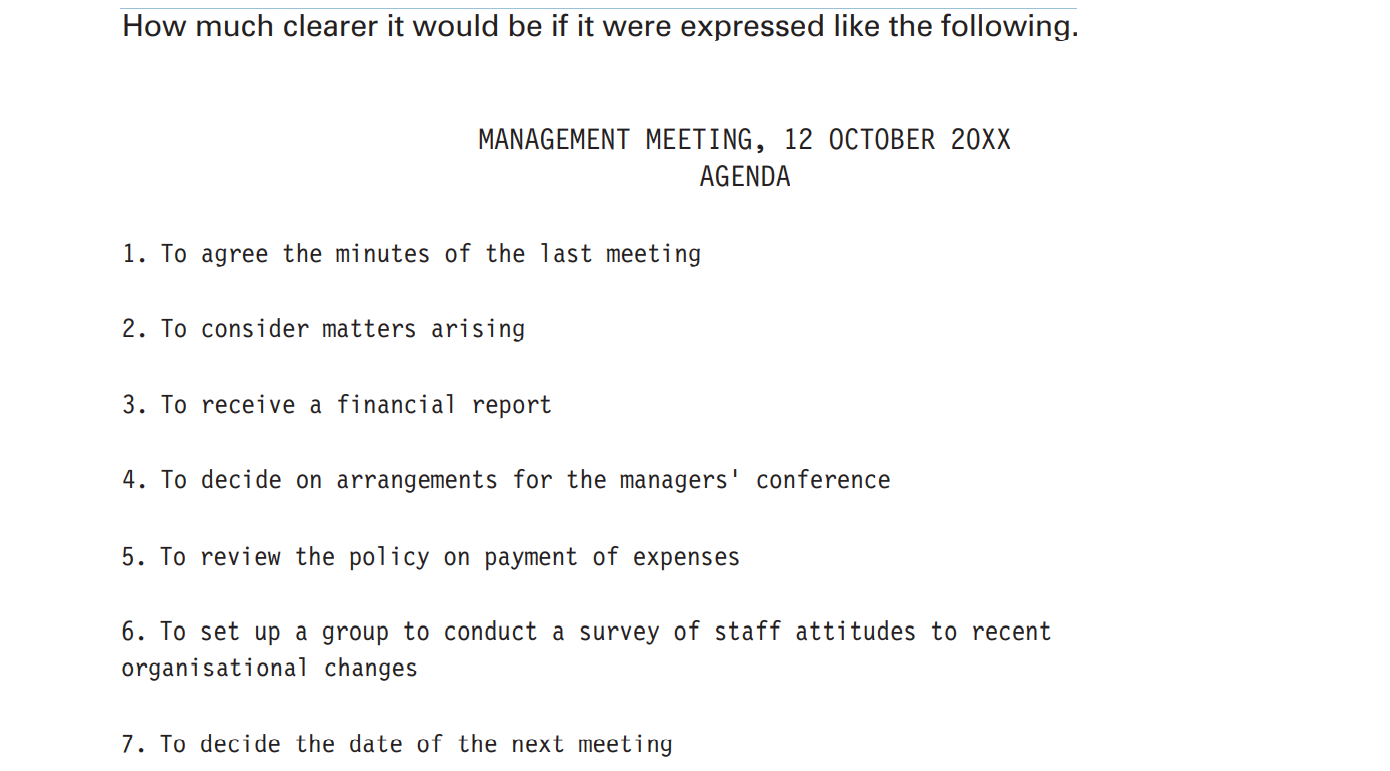

Meetings

Most of us have been to meetings that seem to go on forever, often without any firm conclusions having been reached. This is usually because of one or more of the following problems:

● There is no clear agenda.

● The meeting is inefficiently chaired.

● People wander off the point.

● The discussion goes round in circles, without any clear decisions being made.

These are the characteristics of an efficient meeting.

● The agenda makes it clear what is to be discussed, and which items require a decision.

● Participants are notified of the meeting, the venue and the agenda in good time.

● Any papers that might be referred to are circulated in advance to enable participants to come prepared.

● Someone is delegated to take the minutes.

● Everyone is given a chance to put their point of view before any decisions are made.

● Participants do not stray off the point.

● The discussion does not become bogged down in unnecessary detail.

● Clear decisions are made.

● It does not go on too long. Two hours is generally regarded as the maximum length; after that people’s concentration is likely to be affected.

● Clear minutes are taken and distributed soon after the meeting.

venue: the place where something happens, especially an organized event such as a concert, conference, or sports event.

delegate: a person sent or authorized to represent others, in particular an elected representative sent to a conference.

stray off: move about aimlessly or without any destination.

stray off the point

bogged down: standstill

bogged down in unnecessary detail

The notification should include the following information:

● the purpose of the meeting

● the date

● the time

● the venue (and how to reach it if any of the participants might not know where it is).

uncontroversial: not controversial.

stifle: restrain (a reaction) or stop oneself acting on (an emotion).

arbitrary: based on random choice or personal whim, rather than any reason or system.

tact: acute sensitivity to what is proper and appropriate in dealing with others, including the ability to speak or act without offending.

descend into: to move down into something.

hobby horse: a preoccupation or favorite topic.

I think we have said everything that needs to be said on that subject. Can we move on to the next item?

The basic rules of business communication apply here, just as they do in other circumstances: when you speak you should be brief, clear and direct. You should also avoid being rude. But there are other rules that are particular to meetings.

● Before the meeting, you should read any papers that have been circulated and make a note of any points you particularly want to raise.

● You should bring any papers to the meeting so that, if necessary, you can refer to them.

● You should listen to what the other participants say and respect their views, even if you disagree with them.

● When expressing disagreement, you should do so politely.

● You should not interrupt someone while they are speaking. The only person who should do that is the chair, and only if the person is straying from the subject or preventing others from having their say. If you want to speak while someone else is doing so, raise your hand in a slight gesture to attract the chair’s attention; they should then call on you to speak as soon as it is feasible.

● Being brief means that you should not carry on talking unnecessarily – say what you want to say, bearing in mind all the techniques of brevity we have already discussed, and then allow someone else to speak.

● Do not stray from the subject under discussion.

● Once a decision has been reached, you should not try to reopen the discussion, even if you disagree with what has been decided. You can, if necessary, ask for it to be discussed again at a future meeting, but until then you will have to live with the decision that has been made.

feasible: possible to do easily or conveniently.

brevity: concise and exact use of words in writing or speech.

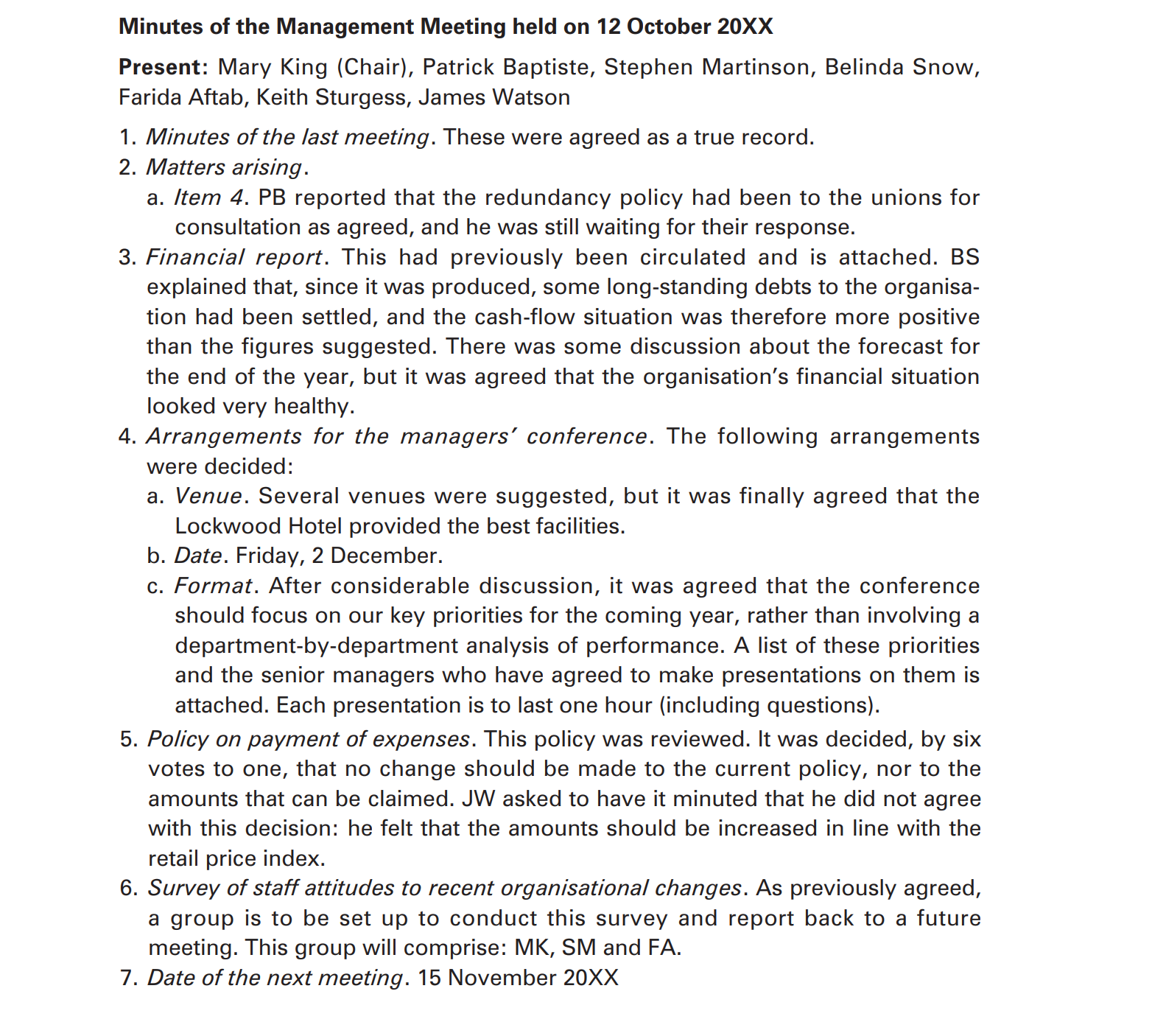

Minutes, also known as minutes of meeting (abbreviation MoM), protocols or, informally, notes, are the instant written record of a meeting or hearing.

Minutes of the last meeting. These were agreed as a true record.

The minutes of a meeting are normally taken by the secretary, whilst the chair conducts the meeting. It is the role of the chair to set the agenda, introduce items, and decide who speaks to the issues. In a very big organisation the secretary might delegate the actual recording of events to an assistant or clerk.

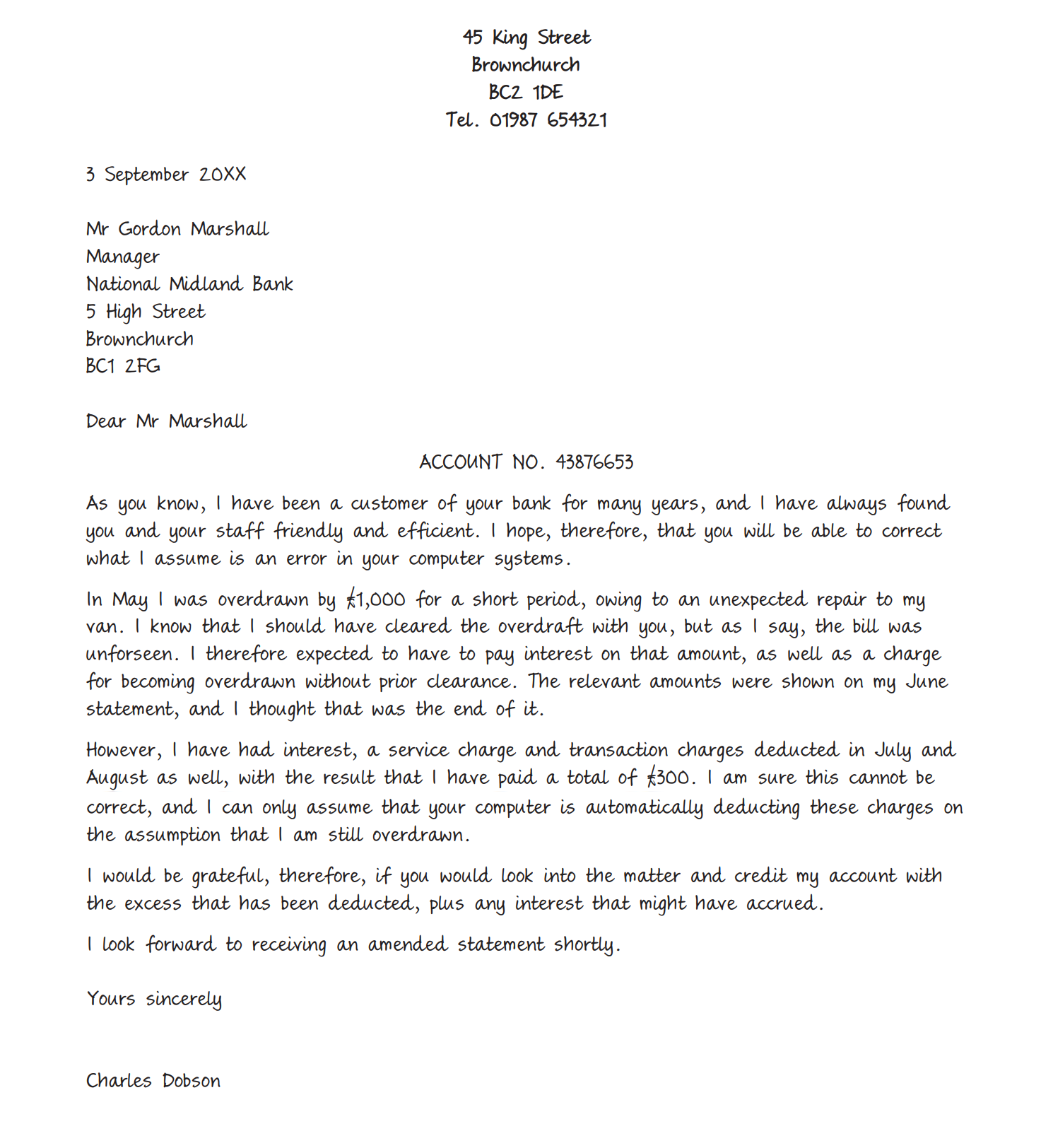

Making a complaint

overdraft: a deficit in a bank account caused by drawing more money than the account holds.

The Four-stage Approach to Complaining

1 Write a friendly letter, e-mail or memo, or make a friendly call, explaining the nature of your complaint and the action you would like taken.

2 If you do not receive a reply, or no action is taken, contact the organisation or person again, still in a friendly way, but take a slightly firmer line.

3 If you still do not receive satisfaction, drop the friendly tone but remain polite.

4 Finally (and this stage should always be in writing), while remaining polite, threaten some kind of action – withholding payment, reporting your correspondent to the authorities, legal action, whatever seems appropriate to the nature of the complaint.

It is important to keep a record of the date on which you took each action and the outcome, if any, even if you are phoning rather than writing. In that way you can refer back to each stage if necessary.

shoddy: badly made or done.

refurbish: renovate and redecorate (something, especially a building).

Before you start writing, you should have two things clear in your mind:

● What precisely are you complaining about?

● What do you want done about it?

It is no use complaining in a general way – about ‘poor’ service, for example, or ‘shoddy’ workmanship or ‘late’ delivery – unless you have specific details to quote. The other person can only take corrective action if he or she knows precisely where things have gone wrong.

Similarly, they can do little more than apologise if you do not say what corrective action you want taken. This action may simply be to improve the service, workmanship or delivery you receive, but even then you should try to be specific. What level of service do you expect? What do you consider a satisfactory delivery time? And of course, many complaints require more specific action – to issue a credit note, to replace faulty goods, or to compensate you for financial loss.

With the answers to these questions, you should be able to prepare your complaint, which should be in three parts:

● a polite introduction, perhaps pointing out the good relationship you have enjoyed with the other person or organisation so far

● the specific details of your complaint

● a request for corrective action

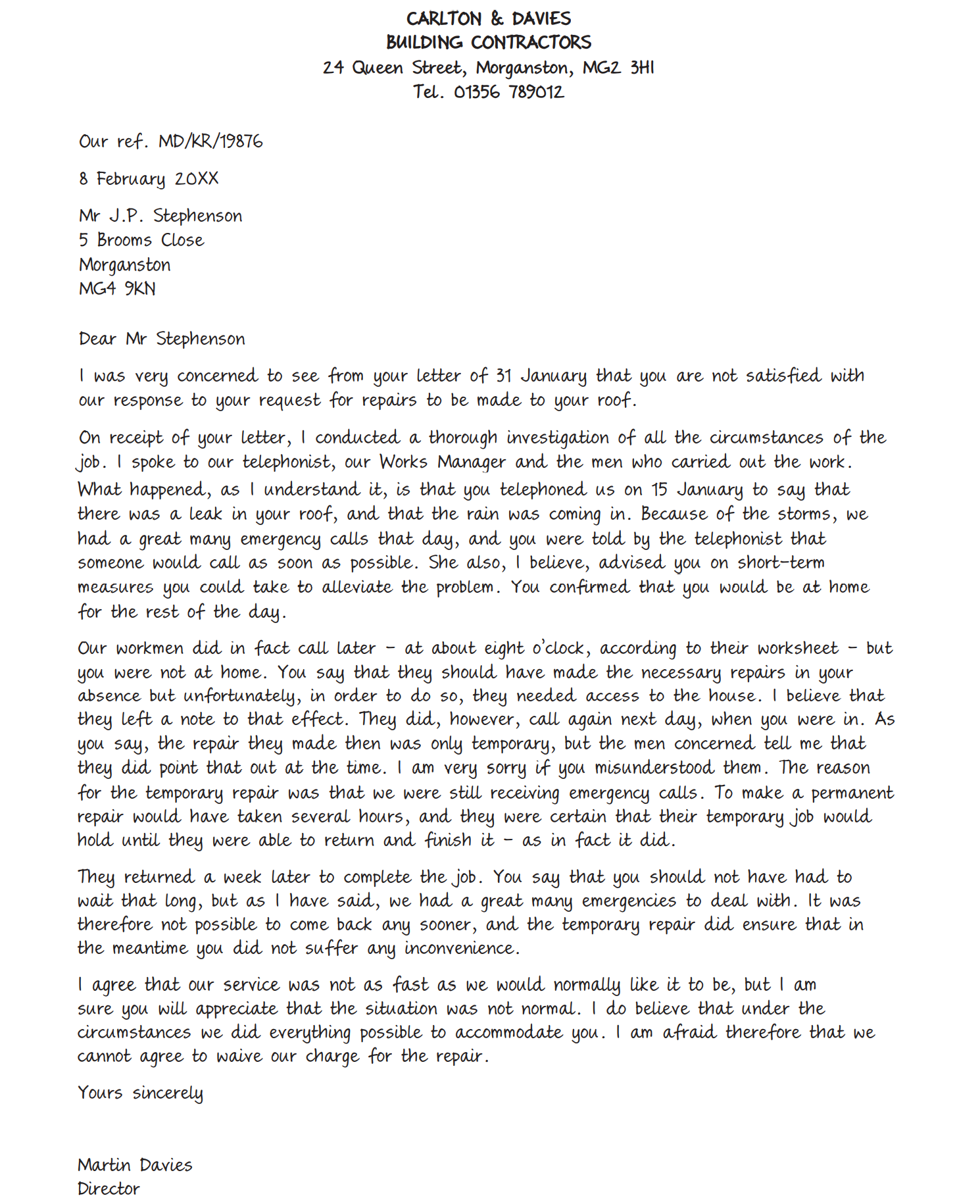

The first thing the person wants is to be reassured that you take the complaint seriously. Too many so-called customer service departments, even (or perhaps especially) in large companies, try to fob complainers off with what are quite obviously standard letters which do not address the nature of their complaints at all. One is left with the impression that they have no interest in correcting any underlying fault in their system.

conciliatory: intended or likely to placate or pacify.

remedy: set right (an undesirable situation).

Even if you are rejecting the complaint, try to find something to express concern about. Here are a few examples of what you might say:

● I was very concerned to hear that you are dissatisfied with our service.

● I am very sorry if our terms of trade were not clear, but if you look at item 12 …

● I am sorry if I did not make myself clear on the telephone.

● I am sorry if you misunderstood the terms of our agreement.

Nobody likes to be told that they are wrong, even if they know that they are – least of all

customers. They might misunderstand or misinterpret things, but they are not wrong.

precedent: an earlier event or action that is regarded as an example or guide to be considered in subsequent similar circumstances.

It could set an awkward precedent and cause a great many problems. If you apologise for a late delivery, for example, when it was the customer’s fault that the delivery was late, then you could lay yourself open to a claim for compensation. Taking another example, if you apologise for poor service, then the customer will expect an improvement. But if you did everything possible to help him or her, you will not be able to make any improvements and the customer is likely to be disappointed again. Express concern about any dissatisfaction, explain the situation fully, apologise for any misunderstanding and be friendly, but state quite clearly that you believe you are right.

It could set an awkward precedent and cause a great many problems. If you apologise for a late delivery, for example, when it was the customer’s fault that the delivery was late, then you could lay yourself open to a claim for compensation. Taking another example, if you apologise for poor service, then the customer will expect an improvement. But if you did everything possible to help him or her, you will not be able to make any improvements and the customer is likely to be disappointed again. Express concern about any dissatisfaction, explain the situation fully, apologise for any misunderstanding and be friendly, but state quite clearly that you believe you are right.

If, on the other hand, you are wrong, you should admit it and apologise. You can even make the other person feel that he or she has done you a favour by expressing your thanks. Here are some examples:

● We always welcome our customers’ views on our service, as it is only through this feedback that we can improve. I am only sorry that we have treated you so badly.

● Thank you for raising the matter with me. Your letter has highlighted a fault in our system which we are now able to correct. I do apologise, however, for the inconvenience you have been caused.

If you use expressions like these, you will show that you are taking the complaint seriously, and that you will not only take corrective action in respect of the person’s actual complaint, but also rectify any faults in your system. Note, too, that in the latter case the writer apologises for ‘the inconvenience you have been caused’, not ‘any inconvenience’, which is a phrase one sees far too often. There is no question about whether the complainant has been caused any inconvenience. The very fact that he or she has had to write or telephone is in itself an inconvenience.

So if you have to apologise, do so unreservedly. Too often people in business try to hide behind bland, formal expressions when apologising, as if trying to avoid responsibility. ‘We regret any inconvenience caused’ is just such an expression. It seems to imply:

● that the writer does not believe that you have really been inconvenienced

● that even if you have, it is not really anyone’s fault, and is a cause for regret rather than an apology

● that if it is anyone’s responsibility, it is the company’s (‘we’) rather than the individual’s (‘I’)

The other way in which people try to avoid responsibility is by making excuses. They give details of how their supplier has let them down, or explain at great length how short-staffed they are, or blame the whole thing on someone who has now left the organisation, and in the process they seem to forget to apologise.

Rejecting a Complaint (The explanation)

● Be polite.

● Express regret or concern that the person has had to contact you.

● Give the impression in your explanation that you have investigated the complaint fully, no matter how trivial it really is.

● Give all the facts as you understand them, particularly where your understanding differs from that of your correspondent.

● If there are any other people who can back up your version of events, then say who they are.

trivial: tiny; of little value or importance.

alleviate: make (suffering, deficiency, or a problem) less severe.

waive: refrain from; give up insisting on or using (a right or claim).

The Remedy

If you accept the complaint, then in the final part of your letter (before you sign off, perhaps with another brief apology) you should outline how you intend to remedy the situation. This could simply involve changes to your systems or your way of doing things so that the same mistake does not happen again. Or it could take a more concrete form, such as giving the complainant a credit note, cancelling an invoice, or paying some form of compensation. It all depends on the circumstances.

But remember that goodwill is important in any business relationship. If you have committed an error or inconvenienced a business contact in any way, it is worth a bit of trouble, and even money, to ensure that the goodwill is not lost. So when it comes to a remedy, err on the side of generosity.

consignment: a batch of goods destined for or delivered to someone.

garment: an item of clothing.

unravel: undo (twisted, knitted, or woven threads).

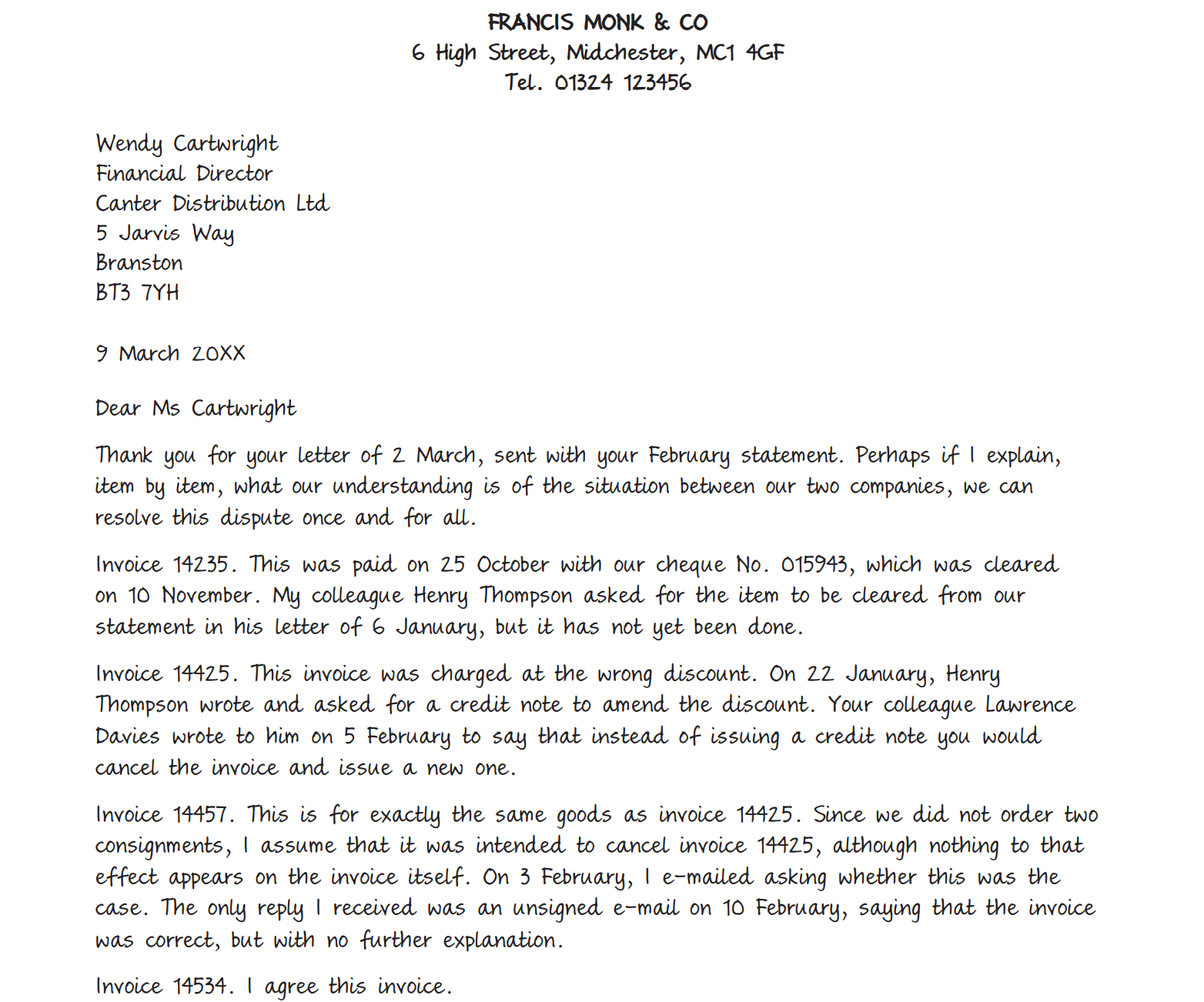

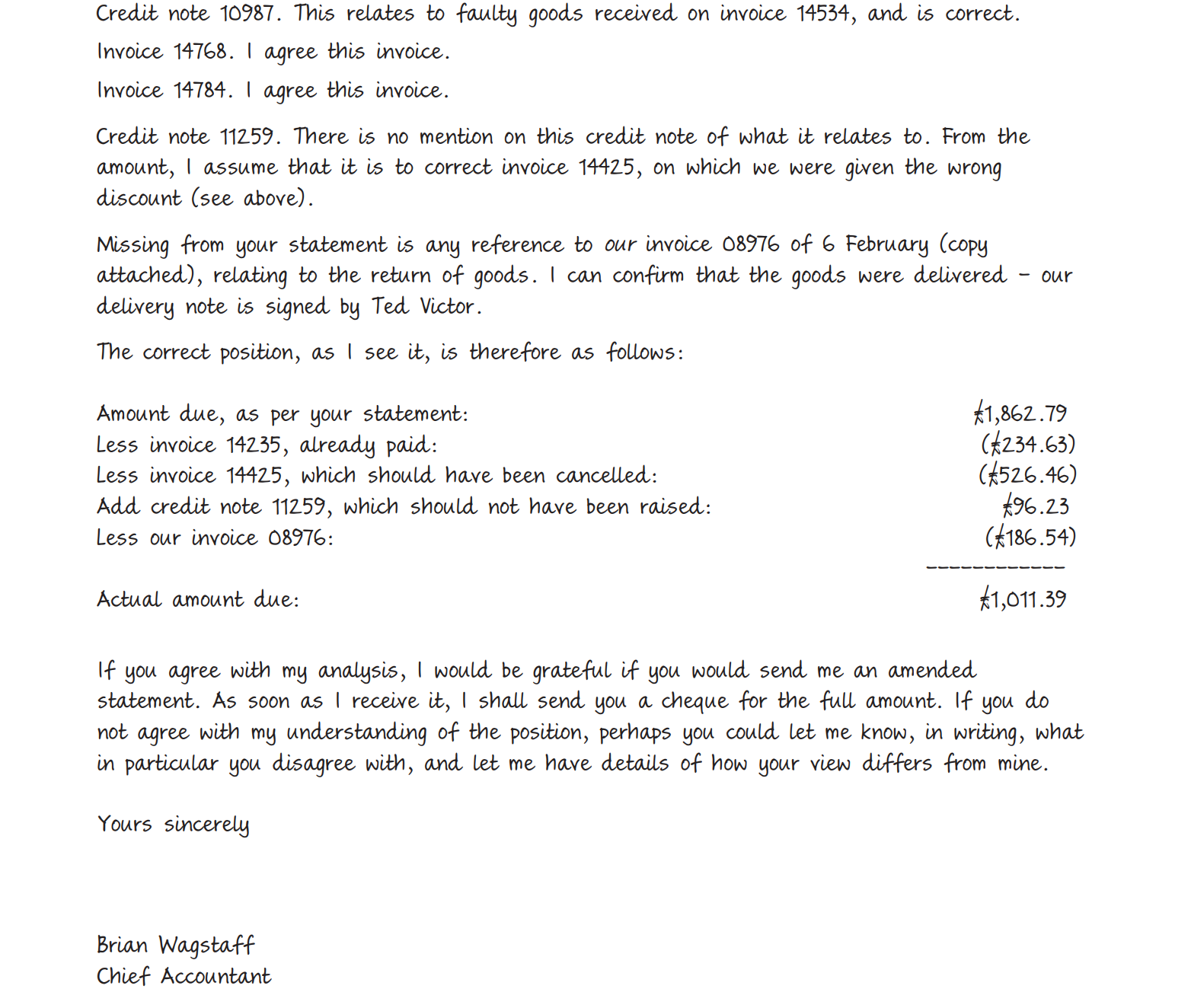

Clarifying Complex Problems

liability: the state of being responsible for something, especially by law.

There are four stages to this task.

- Assemble all the information that is remotely relevant to the situation. This means every invoice, every credit note, every statement, every delivery note, every letter or e-mail received or written, by you or anyone else, any notes of telephone conversations.

- Go through it all, preferably in chronological order. Make sure that you have a copy of every document referred to in the correspondence (and if it is an accounting query, every invoice or credit note referred to in any statements). If there are any items you do not have, and they cannot be found, make a note. Read everything, several times if necessary, until you fully understand the situation. It can sometimes help to make notes as you go along, but however you do it, make sure that it is all quite clear in your mind.

- Write your letter, setting out the situation as you now understand it, in a clear and logical sequence. The clearest sequence may be chronological order, but with certain accounting queries it could be numerical order by invoice or the order in which items appear on a statement. Explain how each document mentioned fits (or does not fit) into the picture and give a summary of the situation (in an accounting query, this will be who owes what, but in other circumstances it will be different – for example, with a contractual problem it might be who needs to take action). If your correspondent

refers to documents you do not have, ask for copies. If you mention documents (particularly invoices, delivery notes or credit notes) which he or she does not appear to have, enclose copies. - Do not give your correspondent a chance to introduce any confusion into the situation. Insist that, if they agree with your analysis, they should take any action you propose, and if they disagree they should indicate precisely what they disagree with and provide documentation to support their case. In other words, ensure that any further correspondence relates to your analysis. And insist that they respond in writing; a telephone call will only provide another opportunity for misunderstanding to arise.

If you follow these four steps, your letter should produce the desired result. But the most important steps are probably the first two. If you do not have all the information in front of you, and if you do not fully understand the situation yourself, then your letter will probably just cloud the issue still further.

preconceived: (of an idea or opinion) formed before having the evidence for its truth or usefulness.

invalidate: (of a document or agreement etc) having no legal force; not valid.

sift: examine (something) thoroughly so as to isolate that which is most important or useful.

concise: giving a lot of information clearly and in a few words; brief but comprehensive.

interpretation: the action of explaining the meaning of something.

Writing Reports: Assembling the facts and seeing both sides

spacious: (especially of a room or building) having ample space.

unviable: not capable of working successfully; not feasible.

equivalent: equal in value, amount, function, meaning, etc.

anticipate: regard as probable; expect or predict.

refute: prove (a statement or theory) to be wrong or false; disprove.

Notice that the writer does not specifically say, ‘It could be argued that … but my counter-argument is …’ The expressions used are:

● The space we have … but …

● Although we do not currently have the necessary software …

● It has been said … but …

● Although some people do not like …

seamless: (of a fabric or surface) smooth and without seams or obvious joins.

decipher: convert (a text written in code, or a coded signal) into normal language.

You need to take into account the fact that…

intrusion: the act of intruding or the state of being intruded (enter with disruptive or adverse effect) especially.

For example, if you are making a presentation on a building project, one slide might say:

This design is intended to provide:

● a carbon-neutral building

● a comfortable working environment

● room for expansion if necessary

● easy change of use in each element

You might show the whole slide and say,

‘These are the essential principles behind this design. They were identified by the clients as their main priorities. We have aimed therefore to combine maximum flexibility with maximum sustainability and comfort.’

Alternatively, you might reveal each line individually and enlarge on that aspect, for example:

● ‘It uses renewable energy sources, and there are facilities to ensure that all waste is recycled.’

● ‘Because it is well insulated, it is also well sound-proofed, and every office has natural light. It is also intended that plants should form an integral part of the layout.’

Leave a comment